SnowMG!

Philadelphia is expecting many of inches of snow, and the weather should start any minute now. It’s safe to say that the city has descended into a full-throated freak-out.

So, let’s put it in perspective with some snow photos from the archives!

Eskimo children playing in the snow at 50 degrees below zero in Point Barrow, Alaska. Notice the dark figures -- because of the bright environment, photographing objects in snow is notoriously difficult. Photograph by William B. Van Valin, c. 1919. Penn Museum image 11328.

Ainu snow shoes (cirru). Collected in Hokkaido, Japan sometime before 1901. Photograph by Francine Sarin and Jennifer Gibson Chiappardi. Penn Museum objects A407c, A407d, image 174442.

Waterproof Parka made of the throat lining of sea lions. Collected by G.B. Gordon in 1905. Penn Museum object NA247, image 149958.

Sphinx of Ramesses II in front of the Main Entrance of The University Museum, covered with snow. The Sphinx was moved into the building in 1916, and into the Lower Egyptian Gallery in 1926. Photograph c. 1913. Penn Museum image 140759.

Convoy en route Teheran-Baghdad on snow-covered highway, near the court of a caravanserai. From the Damghan Expedition, Joint Expedition to Persia, 1932. Penn Museum image 173843.

So remember, if you’re going to go out, bring your parka made from the throat of a sea lion, your snow shoes, your AWESOME mid-1930s truck and the third-largest sphinx in the world.

Tomorrow’s history… today’s elephants

In the archives, we tend to have about a thirty-year lag between something happening at the museum and a researcher wanting to look at those records. However, it’s worth reminding our public that the Penn Museum is actively involved in dozens of research projects, and that the scientists and others involved in this process are creating records every day.

Amy Ellsworth, writing for the Middle Mekong Archaeological Project, has produced one of the more fascinating blogs I have ever encountered. She writes about life on an archaeological dig with humor and a sense of adventure — I would recommend this for anyone who’s interested in archaeology, travel, or who just wants to know what it’s like to ride an elephant.

The Middle Mekong Archaeological Project team is studying caves in the World Heritage site of Luang Prabang in the heart of the middle Mekong River basin, in northern Laos. China is to the north, Vietnam to the north and east, and Thailand to the south and west. As an area at the core of Southeast Asia, yet one that is virtually an archaeological terra incognita, northern Laos can provide some missing puzzle-pieces in several theories on how settled societies developed in the region.

When you’re feeling down…

It’s been a week chock-full of crazy here in the archives (my woo-woo friends tell me that Mercury is retrograde, plus it’s been a full moon. If that means anything). Sometimes, when I’m having a hard day, I go through our database and just try to find cute photos. So here we are.

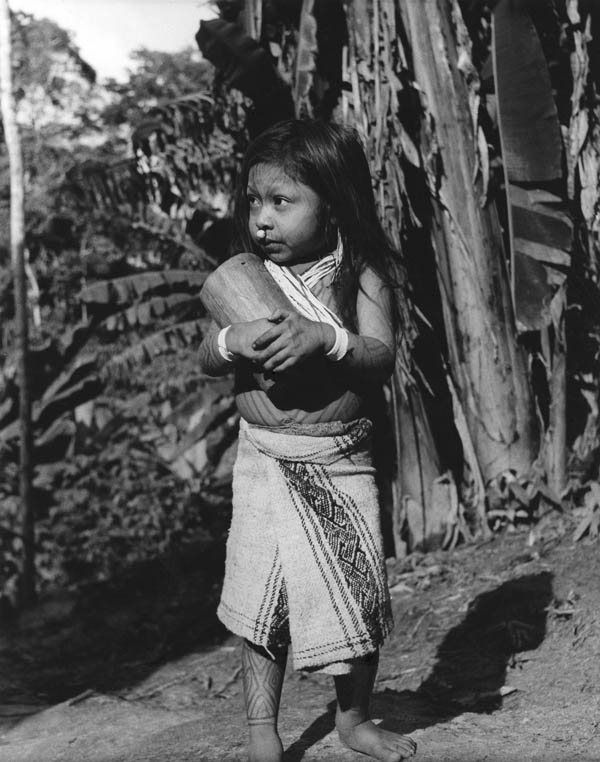

Baxi, a Cashinahua girl with her wooden doll (note the carved eyes and mouth). The designs painted on her body fade after about a week. Peru, 1957. Photograph by Kenneth M. Kensinger. Penn Museum image #148803

Kayak Model. Made of skin and wood, with three human figures, as well as paddles and other accessories from Kodiak Island, Alaska, United States. Photograph by Karen Mauch and John Chew. Penn Museum image #151933

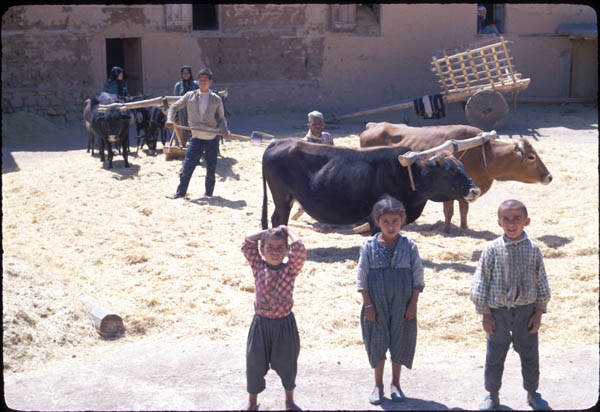

Threshing wheat in Gökpinar, Turkey December 1966. Image by Jacques Bordaz. Penn Museum image #174981

David Randall-MacIver with a donkey in Nubia, Egypt c. 1907. Penn Museum image #175378

Three Cherokee dolls in dresses and shawls. Photograph by Karen Mauch and John Chew. Penn Museum image #151954

Did you say something?

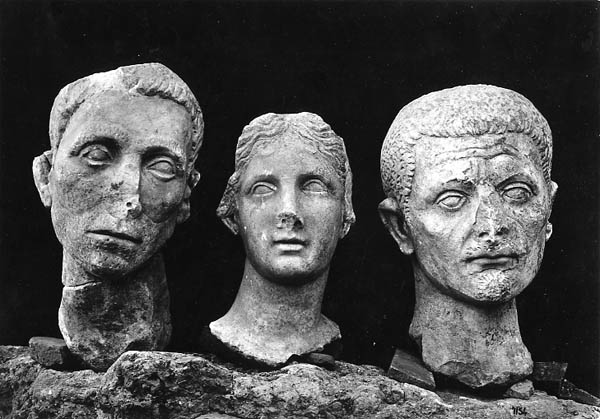

"Muse and portraits of citizens" excavation photo of the heads of three Roman sculptures from Minturnae, Italy, 1931-1933. Penn Museum image #182924

Surely these two guys and a gal have something to say. Create dialogue for them in the comments section — the most clever (by our standards) will win a prize from the archives. Be sure to leave an email address so that we can let you claim your winnings.

Thanks to cellulose and tourists.

It’s great when you find something that is beautiful and also conveys a great amount of information.

This is not one of those circumstances.

But it’s Friday, and we’ve been proofing catalog records all day, and sometimes one just needs to gaze at something very beautiful.

These are photos of two pith books in the collection of the Penn Museum Archives, that we pull out for special visitors. The paper’s cells swell upon contact with the paint, making it appear that the paint is blossoming out of the paper.

These paintings were produced in China in the 19th century, to feed a tourist market for small, portable, and very “Oriental” souvenirs.

Ours came into the museum by way of the Education Department, which collected items from all over the world for the children to observe and touch. Given this history, it is not surprising that the bindings are falling apart, but very impressive how well-preserved the paintings are! We have one album devoted to bugs and butterflies, and one showing Chinese “court” scenes.

It’s really impossible to convey how captivating these are. The images seem to float over the paper, and the colors are rich and full. For cheap-and-dirty souvenirs, these still were the work of great artists.

They don’t have much to do with the history of the Penn Museum. But I hope they’re inspiring, as you plan your weekend activities:

Further Reading:

Preserving Pith Paintings by By Terry Boone, at the Library of Congress:

http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/0305/conserve.html

Two collectors’ descriptions:

http://www.chinese-porcelain-art.com/Chinese-Watercolours.htm

http://www.trocadero.com/paha/items/507777/item507777store.html

Stela! Steeeeeeeela! (Can’t you hear me yella?)

You’re puttin’ me through Hella!

Well, okay, Maya stelae are possibly less immediately dramatic than either Tennessee Williams or the Simpsons. And sure, it’s a different word with a different pronunciation. But the stone monuments in our Meso-American gallery might be my favorite part of walking into the archives in the morning. There’s something about Stela 14 from Piedras Negras that takes my breath away.

Stela 14 in the Meso-American gallery at the Penn Museum. Penn Museum image #160510.

Piedras Negras is a Maya site in Guatemala particularly noted for the beautifully sculpted stelae and hieroglyphic inscriptions it has yielded. The site, located in the northwestern corner of the Department of Petén, Guatemala, along the Usumacinta River, which forms in this area the border between Guatemala and Mexico, was discovered in 1894 by a Mexican lumber man, and brought to the attention of Teobert Maler, a pioneer archaeologist and explorer of the Ancient Maya. Maler visited the site in 1895 and 1899 under the auspices of the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, but conducted no excavations.

A reconstruction of the acropolis at Piedras Negras. Pencil and watercolor drawing by Tatiana Proskouriakoff, 1939. Penn Mueum image #176732

Between 1931 and 1939 the University of Pennsylvania Museum conducted extensive excavations at this site. J. Alden Mason, Curator of the American Section, went to Guatemala in 1930 to select the site and obtain an excavation permit that would allow for the removal on loan to the Museum of half of the monumental sculpture uncovered by the expedition. Mason’s visit also served to make renewed arrangements with Robert J. Burkitt, who was also excavating in Guatemala for the Museum at this time. In December of the same year Mason visited the site again as a member of the Museum’s aerial survey of Petén and Yucatan.

Stela 14 from Piedras Negras, in situ circa 1935. Penn Museum image #15543.

The work of the first two seasons concentrated heavily on building a road to the site through the jungle and the removal of a number of monumental stone stelae and other sculpture, half of which were sent to Guatemala City and the other half to the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Included among these was Lintel 3, dated ca. 750 AD, still considered to be among the most beautiful specimens of Maya sculpture, and Stela 14, shown above, credited with giving Tatiana Proskouriakoff the inspiration for her decipherment of Maya hieroglyphics. The second season produced a new map of the site but also saw part of the camp catch on fire, resulting in the loss of part of the photographic record.

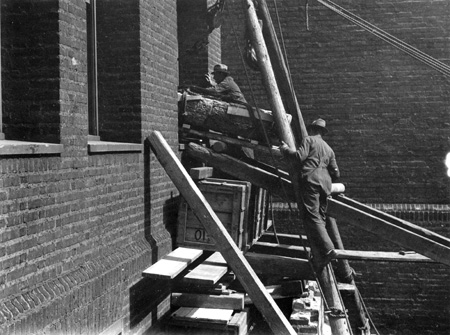

Workers moving Altar 1, Piedras Negras, Guatemala, 1931. Photograph by Linton Satterthwaite. Penn Museum image #15658.

Under Satterthwaite’s direction, the focus of the excavations shifted from the more glamorous task of bringing carved monuments to the exhibition galleries of the museum to purely archaeological questions, such as uncovering architectural remains, establishing building sequences, and stratigraphy. Satterthwaite concentrated heavily on the architecture of the city, excavating a total of eleven temples and seventeen palaces, as well as two ball courts and a number of sweathouses.

Most of the monuments borrowed from Guatemala were returned to the country of origin in January, 1947, after an extension to the original loan. Only Stela 14 and one leg from Altar 4 remain on display in the Museum’s Mesoamerican Gallery today.

Workmen moving stelae from Piedras Negras into the museum, 1933. Penn Museum image #175936.

Moving stelae from Piedras Negras into the museum, outside view, 1933. Penn Museum image #175937.

A number of publications have resulted from the findings at Piedras Negras, but Satterthwaite never finished all the reports he intended to produce. So, intrepid scholars and students, make a name for yourselves by diving into our heretofore unpublished Piedras Negras records!

Ta-DA!

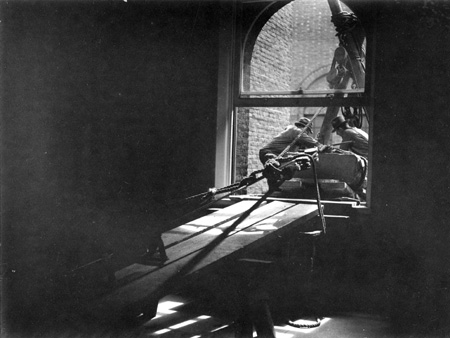

Boy Scouts at museum pageant, April 1945. Penn Museum image #29680.

Guess what! The Penn Museum website has re-launched!

Be sure to visit the new archives pages for information about visiting, our collections and our work.

How to protect your home and family, the Sassanian way.

Ok, I’ll be honest. At first I just chose this image of an Aramaic incantation bowl as the fun friday image of the week because: “look! cute child-like monster drawings!”.

Penn Museum object B2945, image #152805. From Nippur (present-day Iraq).

But the more I learn about this esoteric corner of the archaeological world, the more relevant these little bowls become.

For several hundred years between 400 AD and 700 AD, when much of what we call the Middle East was under the influence of the Persian Sassanid Empire, these bowls were produced. Inscriptions in various dialects of Aramaic were painted on the bowls, (or inscribed in metal sheets or stone amulets) generally naming a long list of demons, spirits, and evil beings that were to be kept from harming the owner. For added emphasis and power, sometimes the demon itself would be drawn.

The inscriptions were probably produced by local magicians or scribes, but ordered by individuals who hoped to rid themselves of some persistent problem. Some bowls are customized with the owner’s family members’ names, or with a specific problem, such as to protect them from “the curse of the employee and employer who stole the wage and from the curse of the brothers who did not divide truthfully among themselves and from the curses of all people who curse in the name of idol demons”. [1]

What is both intriguing and frustrating to the scholar is their variety, and inconsistency. These objects contain texts in several different scripts, and many separate dialects of Aramaic. Late antiquity was a time of a great proliferation of religions, and the bowls appear to have been used by members of Zoroastrian, Jewish, Christian, Mandean, Islamic, and pagan groups. A single bowl will often name deities associated with several religions, and use magical words or phrases from more than one tradition. It seems that the users of these objects often tried to ‘cover their bases’ by invoking any powerful spirit they could think of – from any of their neighbors’ religious traditions – either for help or censure.

Like all archaeological specimens, these objects can tell us things about many different aspects of life in Iran and Mesopotamia in late antiquity. We can learn about family structure, naming traditions, literacy levels, socioeconomic pressures, and religious practices. What is exciting to me about these bowls, particularly, is the insight they provide into the religious syncretism that may have been commonplace in these communities.

The syncretistic features of incantation texts reflect a society where the members of different religions living side by side shared many ideas and practices on the level of popular beliefs and customs that were not necessarily accepted by the leaders of those religions.(Morony, 2007).

The invocations weren’t always positive – often the gods of one group were transformed into demons by another – but these objects show how aware they were of each other. It’s always good to be reminded that we’re not the first multi-cultural, globalized society, and to see how others have done it before.

In the meantime, keep an eye out for this guy:

Penn Museum object B16017, image #141859. From Nippur (present-day Iraq).

Sources/Further Reading:

[1]: Bohak, Gideon. 1995. “Traditions of Magic in Late Antiquity”, a web exhibit. http://www.lib.umich.edu/files/exhibits/pap-/magic/intro.html

[2]: Morony, Michael G. 2007. “Religion and the Aramaic Incantation Bowls”. Religion Compass, vol. 1, no. 4. pp 414-429

Noegel, Scott B, Joel Thomas Walker, and Brannon M. Wheeler. 2003. Prayer, magic, and the stars in the ancient and late antique world. Penn State Press.

Corbett, Joey. Word Play: The Power of the Written Word in Ancient Israel.

Turtle Heist

We’ve all been told that anthropologists have no right to intervene in the lives of their subjects — does it make a difference if their subjects are small, green, and promise not to tattle?

Frank Goldsmith Speck, near the end of his career at Penn, befriended John Witthoft, a young colleague of his. The two had much in common — both were interested in Native American people, and neither were terribly interested in the fashions and pretenses of their peers in academia.

Speck came to the University of Pennsylvania in 1907 as a Harrison Fellow in anthropology, and received his Ph.D. in 1908. Considered one of the founders of anthropology at Penn, Speck organized the department of anthropology in 1913, and for forty years he was the senior member. John Witthoft studied with Speck; he joined the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania in 1966 and retired in 1986 as associate professor emeritus, specializing in the archaeology and ethnology of Native Americans.

One day, near the end of Speck’s career and the beginning of Witthoft’s, the two decided that the turtles under the care of the Philadelphia Zoo were longing for the outside world. The two snuck into the zoo one night, loaded them into a truck, sprung them, and transported them to what they thought would be a more congenial environment — a pond in Swarthmore, Pa.

Unfortunately, the always-intrepid Philadelphia police were able to trace the truck to the two turtlenappers, who were then asked to either reimburse the zoo for the two turtles — to the tune of $600 — or return them to the zoo.

This is where I would like to take a minute to imagine these two important names in the history of anthropology wading in a pond in the middle of who-knows-where, trying desperately to remember which were the turtles they stole and which were run-of-the-mill pond turtles.

Upon their return, the zoo director produced a receipt for their return and promised to upgrade the turtles’ environment.

“All the thoughts of a turtle are turtle” Ralph Waldo Emerson. I can't believe that I'm saying this, but this is probably not the turtle that Speck and Witthoft rescued. Courtesy of flicr user ricmcarthur.